By Allison Malafronte

Charlie Yoder in his East Hampton studio

Charlie Yoder’s paintings have a larger-than-life presence. Usually occupying the better part of a gallery wall, they command your attention with their graphic rhythm and realistic detail, offering as much intrigue and mystery as the actual scenes in real life. This is an appropriate way for the six-foot-eight artist to work, as it matches both his temperament and the dramatic light-and-shadow views of nature to which he is drawn. Facile in numerous forms of media and genres—painting, design, linocuts, monotype, silkscreen—and driven by both big-picture abstraction and close observation, Yoder has been flexible enough throughout his life to move in different stylistic directions as needed, merging various influences and discoveries until he found his artistic voice.

Yoder had a most interesting and formative experience as a young artist living in New York in the 1970s and 1980s. In addition to becoming the director of modern-art mogul Leo Castelli’s print gallery, Castelli Graphics—which sold the prints of such Pop Artists as Andy Warhol, Jim Rosenquist, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and more—Yoder was also the curator for the famous painter Robert Rauschenberg for more than ten years. He traveled with the artist around the world, installing and de-stalling his retrospectives and observing first-hand the life of an internationally recognized artist who wasn’t afraid to combine different media and color outside the lines.

Eventually, it was time for Yoder to refocus on his own art. A few major life events—including an artistic epiphany in the moonlit woods in the winter of 1997 and the discovery of Simon Schama’s Landscape and Memory book—led him on the path he is currently on now: out in the middle of nature, meditating for as long as needed on a powerful scene, extracting the essence of what makes the view visually compelling. In this Q+A, Yoder documents that journey in journal-like detail, sharing several stories, chance encounters, and surprises along the way.

AM: You initially studied illustration at Pratt Institute, eventually concentrating on printmaking, silkscreen, and painting. Today you continue to work in many different media: oil, acrylic, monotype, linocuts, silkscreen, etc. How would you define your style/the melding of those media?

CY: I entered Pratt as an illustration major but quickly found that having other people in control of my art was not interesting to me. I switched to fine art, where I concentrated on silkscreen and lithography. I had not done much painting at this point and was uncomfortable with it at first. Three teachers were patient and supportive: Michael Lewis, James Gahagan, and Jake Berthot. Their attention is still appreciated. Still, I feel that going to museums and galleries and hanging out with other artists exposed me to most of what I know about art.

Charlie Yoder, A Light Touch, 2005, oil on canvas, 48 x 62 in.

AM: When you were in your twenties you landed your first job at Castelli Graphics, started by the famous contemporary art dealer Leo Castelli. Was this the place where the prints were produced or the gallery where they were exhibited?

CY: Castelli Gallery was a retail graphics outlet for the artists that Leo represented. The inventory came from several sources. Sometimes, the artists would consign work they had had published by professional printers. Sometimes the gallery would buy work from publishers and/or fine-art print shops. Other times we would, singularly or in partnership with others, arrange a deal between the gallery, the artist, and a print shop to do a limited fine-art print. Leo’s gallery showed unique pieces of art and Castelli Graphics showed limited-edition prints and multiples (limited-edition sculpture). These were called original limited numbered editions. My boss was Toiny Castelli, Leo’s second wife.

I was in my last semester of school when I started working there part-time in the summer of 1971. My original tasks were to make trips to the post office, run errands, clean and wax the floors, and wipe fingerprints off the walls. I would hang shows under Leo’s supervision and show art to customers as directed by Toiny. When I graduated from Pratt with a B.F.A., I was hired full-time. Having experience in printmaking served me well, as no one at work knew the difference between one print medium and another.

Charlie Yoder, Color Field, 2014, acrylic and oil on canvas, 38 x 56 in.

I soon met many people involved in the contemporary art world: artists, collectors, gallery owners, art writers, and assorted hangers-on. Leo’s artists were Post- Abstract Expressionists such as Jasper Johns and Bob Rauschenberg and Pop artists such as Andy Warhol, Jim Rosenquist, Roy Lichtenstein, and Claes Oldenburg. Other big-name talents were Frank Stella, Richard Serra, Ed Ruscha, Keith Sonnier, Don Judd, Dan Flavin, and Bruce Nauman. Strangely, or maybe not so strangely, I had no real sense of how special and unusual a job this was for a young artist freshly arrived from Maine. That realization came much later. It was interesting work with interesting people and paid a living wage. I considered myself lucky. Still do.

AM: You must have many colorful stories and memorable encounters from working there. Can you briefly share one?

CY: To briefly share one experience would be to give short shrift to so many experiences. Which to choose? The wildly drunken wine-tasting Sunday brunch in Dan Flavin’s home studio in Garrison, New York with the owners and staffs of three of the galleries that showed his work and the stumbling romp with selfsame staffs through the woods afterwards? At the Factory when I was talking to a friend about witnessing a shooting and how surreal it was and I didn’t see Andy standing next to me … he responded “Yeah. Even when it happens to you, it’s like you’re watching TV.” Being around Ed Ruscha and his beautiful movie-star girlfriends? Getting to know Keith Sonnier and all the sculptors, painters, musicians, dancers, photographers, and performers from Louisiana and their friends? Such fun.

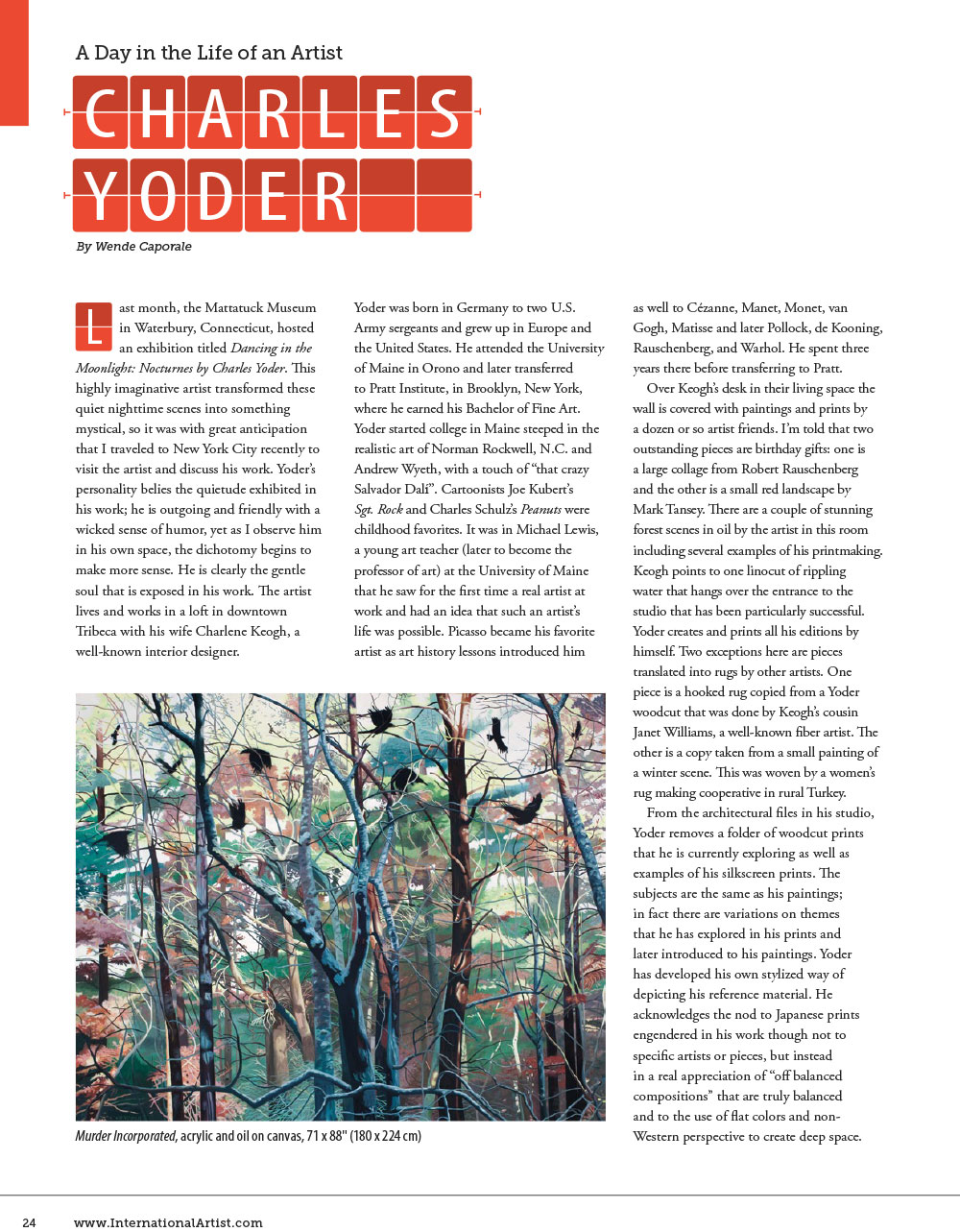

Charlie Yoder, Murder Incorporated, 2010, acrylic and oil on canvas, 71 x 88 in.

AM: You obviously met Robert Rauschenberg because he asked you to be his curator, which you did for twelve years after leaving Castelli Graphics. What influence did being in his world and seeing art through his eyes have on your own work?

CY: Of all the artists, the one I most connected with was Bob Rauschenberg. Even before working at the gallery, I was a big fan of his work. His silkscreen paintings and lithographs drew me to printmaking. The first time I met him he grabbed my head with both hands and kissed me square on the lips and said, “Hi. I’m Bob.”

Eventually I learned more and more about the gallery business and was given more responsibilities. I got good at hanging exhibits and talking to clients and artists. One perk was invitations to openings and parties. Bob threw the wildest parties. They were always open door. Whoever showed up was welcome. That is, up until the night when the crowd got out of hand and there was mayhem throughout the whole house. The evening culminated when sculptor John Chamberlain showed up blackout drunk and started a fight with another sculptor Richard Serra and the two of them were grappling with and cursing each other on a large foam Chamberlain couch. I was sitting on that couch right next to them when Bob came over and pulled them to their feet saying, “OK, girls. Break it up.” The next day Bob said there would be no more parties like that. “They’re not fun anymore.”

I was at the gallery for about five years and was the director when I left. I consider this the beginning of my Master’s degree. Shortly after, Bob asked me to be his curator in his New York studio/home. The work was much like what I had been doing at the gallery, just much more involved. He had a great bunch of people working with him, and it was a fun and interesting environment.

Bob was supportive of the artists who worked with him, but also expected a lot of time and effort to be spent caring for his needs. He traveled constantly internationally and back and forth from the East and West Coasts and between New York and Captiva, where his main studio was. My art took second place. I found hanging with Bob was an easier way to be a part of the art world than me working in my studio and slowly finding my own place. I was painting and showing my work but definitely not enough of either one.

I worked with him for twelve years off and on. I crisscrossed the States installing his U.S. retrospective, installing five museum shows. I traveled to Europe with another retrospective to a total of six cities in Germany, Denmark and ending up in London at the Tate. Burned out and frustrated with not getting my own art done, I told Bob to fire me, and he did. I was enjoying teaching printmaking at the School of Visual Arts and soon became a construction worker, work that I really did not like. It served a purpose though. It made me realize that I much more preferred making art than “putting up sheet rock and mudding.”

I started painting more and showing more. I met a tall good-looking blonde interior designer named Charlene and we hit it off. We were quickly “an item.” Then Bob called one night and asked me to work with him on the ROCI world tour. I couldn’t say no. It was to be a five-year tour around the globe installing an ever-changing retrospective with new work added to each venue: Mexico City, Santiago, Chile; Caracas, Venezuela; Beijing, China; Lhasa, Tibet; Tokyo, Japan; Havana, Cuba; East Berlin; Moscow; and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. I’d travel to each country, unpack and install the show, sightsee, and return to the States. Then I’d return to the current country, take down and pack up the show, and take it to the next country and start all over again. This was the routine more or less with some variations for the next four-plus years. The biggest variation in the plan was me quitting after Cuba. The tour went to East Berlin and Moscow without me. Then Bob called and asked me to be in on the finish of the tour in Kuala Lumpur. I couldn’t say no. Charlene met me there and after the opening, we went sightseeing in Bali and Java.

Charles Yoder, Short Cut, 2006-2007, acrylic and oil on canvas, 52 x 160 in.

Thus ended my employment with Bob Rauschenberg. We remained friends until the end of his life, but our working together was done. There are a couple of things that I picked up working with him. One is that anything can be art. All you have to do is say it is. Bob changed his work constantly, and he could make anything look beautiful. Knowing this made my abrupt switching from abstract to realism a lot easier. The other lesson was that you have to work constantly to get solid consistent results. These were important lessons.

A couple of things, both very different, happened in my life that brought about important changes. The tall blonde and I moved in together and got married. Married life agreed with me. I spent more time in the studio, got more work done, got a gallery, had shows and started selling artwork. The other important change came with the loss of a very good friend, Al Taylor. Al was a sculptor, draftsman, and printmaker, whom I came to know when I started working for Bob. Al’s girlfriend Debbie was Bob’s curator, and I became Bob’s curator when she quit to work for Leo Castelli. Really a small world, wasn’t it?

Al and I worked together for about three years or so at Bob’s and became very close. We spent a lot of time together after work as well, bars and clubs and art shows and the like. After he stopped working for Bob, our friendship continued. He got a studio on East 19th St. and Park Ave. South. On many afternoons around quitting time, I would meet there with other mutual friends and we would drink and smoke and talk and listen to music. During these get-togethers, Al would be the only one working. He was always working making the most beautiful, lyrical and, often, very witty works. His early death shook me. I realized that I had been taking my life as an artist for granted. I was delusional to think that there was plenty of time to get work done. To develop a body of work that was worth something, or important to me at least. To get it out into the world. Al was a month older than me, and it became clear that if I wanted to get anything worthwhile done, I had to take more control of my time.

AM: I know that back in 1997 you had an artistic epiphany in the woods at night. In your own words, what happened in that moment?

CY: A couple of years before Al died, I had that epiphany that I’ve talked about. I had been dissatisfied with the large abstract paintings I had been doing. These were eight-foot by five-foot swirls of monochrome oil paint on canvas. They were pretty, but I found them ultimately repetitive and restrictive. I had mixed some imagery and text into some of them but they still weren’t clicking. What I’m doing when I create does not always follow the original “logical, well-thought-out, predetermined” course. I may think it will happen, but it seldom does. Something sparks a beginning and when it’s done, I find myself justifying the “predetermined plan.” Why I did what I did becomes a bit of fiction. Maybe it’s better described as an alibi.

One winter’s night around 1997, I was out in my backyard in Northwest Woods in East Hampton in the middle of a stand of tall pines. I was ankle-deep in snow watching the light of a full moon shining down through the boughs and the shadows it made dancing across the bright white snow. I was struck by how beautiful it was. It was so simple, but it had everything I was looking for in art-making. Light and shadow. Rhythm and tempo. All I had to do was look and copy it.

Charles Yoder, Tree Rings, 2012, one-color linocut, 16 x 26 in., edition 14.

AM: Please compare and contrast what your life as an artist was like before this breakthrough and then after. Have you had any additional types of realizations or important “game-changers” in the studio since?

CY:I thought it was going to be really easy but, of course, it wasn’t easy at all. But that moment excited me and got me started on the journey I’m still on. The first painting took three months of many trial-and-error efforts before I got a result I was satisfied with. Over time, I came to realize that all seasons, all times of day and night, all weather conditions, and all venues of nature were worthy subjects to study and that also dealt with realism and abstraction.

I had read Simon Schama’s Landscape and Memory, which was about the influence of a nation’s geography on its self-image. It was broken down into four chapters: woods, water, rock, and a combination of the three. I thought this was a perfect outline for a career. I’d spend five years with each section and end my life working on the fourth chapter. I couldn’t foresee how fascinated I’d become with “the woods.” Each time I would do one of the other three, I’d find something that pulled me back. Again and again, I’d see something that grabbed my interest. This was the glimpse that brought on a meditation of looking until I saw. Looking for the essence of what was so special. Sometimes I’d start painting right away. Other times it’d take four or five years of sketches and watercolors, even print editions before the painting began. There was no rhyme or reason of how it would proceed.

I continue to find artists that spur new explorations like Fairfield Porter, Lois Dodd, Neil Jenney, Matisse, Monet, Bonnard, Vuillard, Hokusai and Hiroshige. Rauschenberg still gives me permission to do anything I do. I find that the more I look, the more I see. The more I paint/draw/print, the more accurately I can depict that special moment that attracted me in the first place.

AM: Your paintings are created large-scale (sometimes very large-scale), which best suits the kind of expansive vistas and dramatic light effects you are capturing. Finding a place with enough space to exhibit that type of work can be challenging. If you could build or commission the creation of the ideal space to show your work, where would it be?

CY: Years ago a painter friend castigated me for making small paintings.

“You’re a big man. Make big paintings,” he said. It made sense. I like large paintings because it fits my arm span and the space I occupy. I like the idea of experiencing paintings that involve time and space. I’m aware of the absurd reasoning of making objects that so few people can accommodate. No matter what the size, there is really no logical reason to make art. So size doesn’t enter the equation other than some sadomasochistic urge to have desire met with a certain degree of disinterest. Of course, having said how futile this activity of making large-scale work seems to be, I know that out there in the world are large corporate lobbies, board rooms, and the mega-mansions of billionaire art collectors. I saw Rauschenberg fill them. I am currently satisfied with the size of my painting walls, which are about eighteen to twenty feet wide. At this time in my life as a working artist, affordable and sustainable storage is a big concern.

Charles Yoder, Once in a Blue Moon, 2014, acrylic and oil on canvas, 40 x 64 in.

AM: You currently have a solo show on view at the Atelier at Flowerfield titled Natural Resources that highlights a selection of your work from the last twenty years. What was it like to see all of those paintings in the room at once? Is there anything you can see in the work from your perspective now that perhaps you couldn’t see then?

CY: The current show at the Atelier at Flowerfield is an unexpected and welcomed gift. Kevin and Margaret McEvoy have offered me the rare opportunity to show many of my large works. Full Circle is a triptych portraying the four seasons in a single day. It measures four feet by twenty-four feet and from start to finish took nine months of working every day. Borderline and Short Cut are fourteen feet long. My studio allows a viewing distance of about nineteen feet. Atelier Hall offers about thirty-five feet or so. The compositions, rhythms, and color changes look so different to me from these distances. I’m enjoying looking at these with “fresh eyes.” To see twenty years of work in one place has reinforced my belief that I am mining a rich vein of material. The paintings have not become easier. They just continue to pique my interest.

AM: You have said that you see each painting that you make as a mediation on a glimpse, and you have also alluded to musical metaphors. Would you also say that light is also an ascendant theme in the majority of your work?

CY: I believe that all art involves degrees of light from full on to none at all…from too bright to see to too dark to see. All our senses respond to the different degrees of these rhythms and, as such, I see all this work as akin to musical compositions. Rhythms and tempos of light and shadow are as essential as are different values and timbres.

A good piece of art sings.

AM: I understand you are very involved in the Artists' Fellowship. Please tell us a bit about your role with this organization and the types of assistance and help it offers fellow artists.

CY: Thanks for asking. I became President of the Artists’ Fellowship, Inc. two years ago. The Fellowship is a 159-year-old charity that provides emergency aid to professional artists in dire financial need. A fully volunteer board meets monthly to go over requests to help pay late rents, medical bills, fire or flood damages as well as other unexpected contingencies that artists’ lives are subject to. A majority of this board must be working professional artists. Last year we were able to give $270,000 to fifty-one artists. It’s a real honor and privilege to be involved with such a wonderful organization.

Charlie Yoder in front of his acrylic and oil painting, Four Play, 2016, 4’ x 24’